“Long games and short games. You can’t afford to roll the dice when you’re poor.”

My friend Parth said this when we first met, and it stuck with me for over a year.

When it came out in 1970, the Stanford marshmallow experiment claimed to predict success in later life by measuring kids’ ability to delay instant gratification. You can have one marshmallow now, the 4- and 5-year-olds were told, or you can have two when I come back to the room. The kids who held out for two marshmallows reportedly fared better in academic achievement, social skills, mental health, and capital formation (e.g., investing in future-oriented activities like education and exercise).

Per the study’s author, Walter Mischel:

At age 27-32, those who had waited longer during the Marshmallow Test in preschool had a lower body mass index and a better sense of self-worth, pursued their goals more effectively, and coped more adaptively with frustration and stress. At midlife, those who could consistently wait (‘high delay’), versus those who couldn’t (‘low delay’), were characterized by distinctively different brain scans in areas linked to addictions and obesity.

Surely, we just need to teach pre-schoolers to resist temptation!

The solve, it turns out, is not so simple.

In the decades since, the inability of researchers to replicate the experiment points to other possible factors that affect kids’ ability to wait for that second marshmallow. One study, published in 2018, found the benefits of delayed gratification were not nearly as significant as those found by Mischel—and in fact disappeared by age 15 after controlling for family and parental education.

For kids in poverty, life has few guarantees.

Food today might not be there tomorrow. A promise today might not hold weight in a week, when circumstances change and there are new bills to pay. Poor kids don’t have the same luxury of weighting the future in decision-making. Instead, they’re more likely to focus on solving for the present—often at the expense of future goals.

Poverty also affects your perception of1:

Life authorship (e.g., you disbelieve your actions can shape your outcomes)

Risk aversion (e.g., you conform to safe choices for financial security)

Social exclusion (e.g., you feel excluded from or unjustly treated by society)

From 2008 to 2018, I volunteered with the United Nations Children's Fund and traveled as a field reporter for Voices of Youth, a UNICEF-sponsored publication with readership in 180 countries. When the pandemic hit in 2020, I led U.S. crisis response for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s support of underserved K-12 schools and students in the transition to remote learning.

For kids in poverty, bad choices aren’t inherently “bad” but adaptive.

My #1 mindset unlock from a decade in philanthropy-funded education, which some struggle to intuitively grasp, is this: For kids growing up in poverty, what may look like bad choices aren’t inherently “bad” but adaptive for their circumstances.

Just as bad emotions aren’t inherently “bad” but a signal that something might be misaligned (i.e., the “check engine” light alerting us to check in with ourselves), so too are bad choices often the result of external, out-of-control factors for kids in poverty. Rather than blame kids for lacking the willpower to resist the instant marshmallow, we should examine the societal and structural scarcities that force 4- and 5-year-olds into functional decision-making.

You can’t afford to roll the dice when you’re poor.

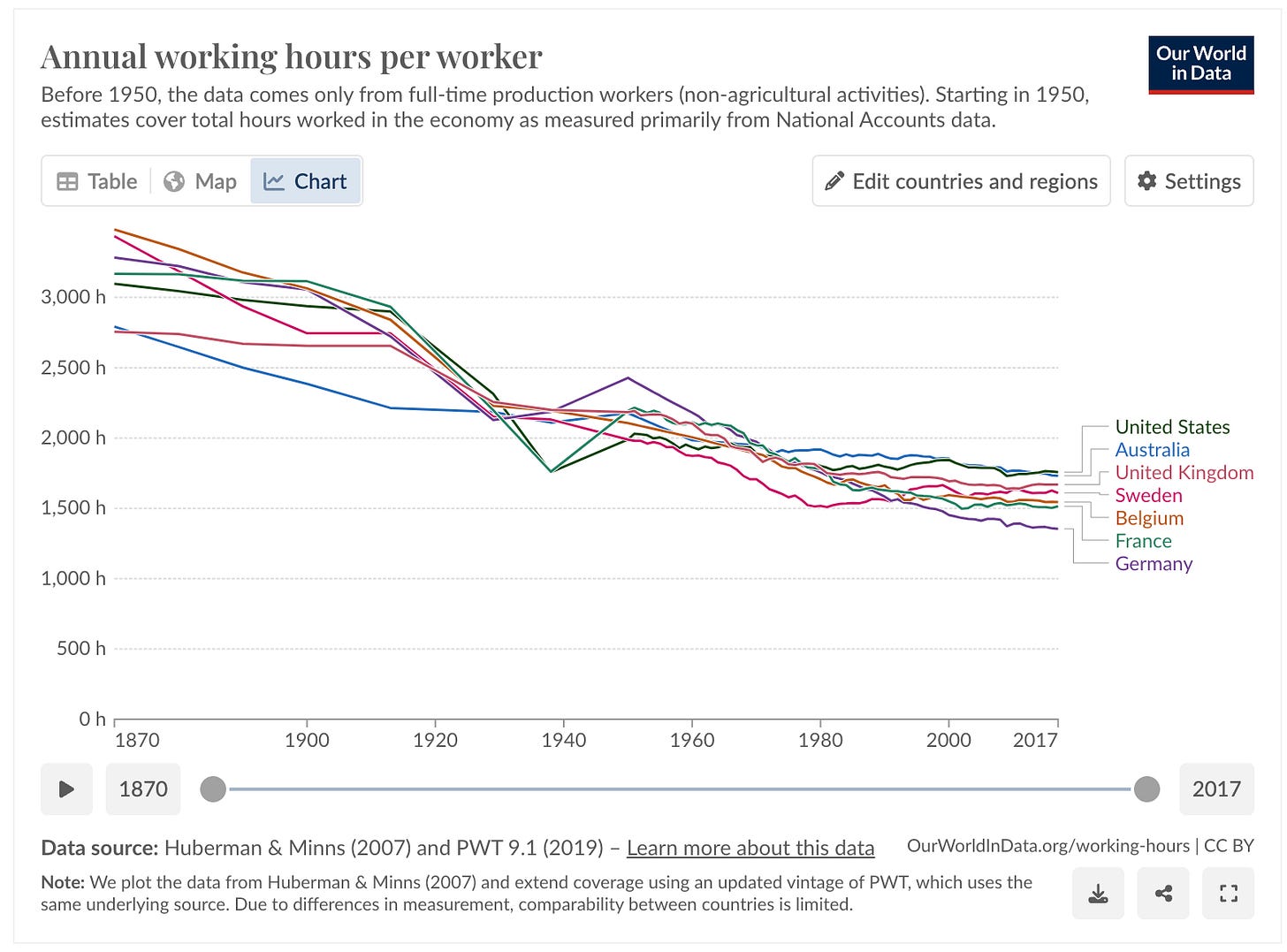

AI is already adding to global aggregate production. I’m also optimistic that AI can improve daily-life outcomes for the average worker. My belief stems from Keynes’ 1930 prediction that his grandchildren will be working 15-hour weeks in 100 years—thanks to machines and technology that augment labor productivity. While we’re far from Keynes’ leisurely prediction of 15 hours a week by 2030, workers around the world are still working measurably less than before the 2nd Industrial Revolution:

My college wifey roommate just finished her MBA/MPA at Wharton/Kennedy. (Go Amy!) Another friend, Jeremie, recently left a lucrative career in enterprise software to pivot into tech policy at SIPA.

It’s an incredible time to be working in policy. This is not the time for “trickle-down economics”, which is free-market mythology and a dressed-up way of saying the poor can starve for table scraps.2 With global productivity enhancements from AI, we have a shot at restoring the value of a promise for all kids.

We need conscious policy intervention if we want AI to benefit all of humanity.

We need more people like Amy and Jeremie.

For more on the intersection of poverty and decision-making, I recommend this 2017 research study funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in the UK.

The 2022 World Inequality Report is a masterclass on global economic resource distribution from 4 of the world’s leading economists (Chancel, Piketty, Saez, Zucman). Policy can correct shortcomings and externalities of laissez-faire markets.