This meditation on 20th century medicine, socialism, and citizenship is heavier than my usual writing. If you’re feeling low, here are more uplifting reflections from 2024: on optimism, trust, authenticity, friendship, commitment, intimacy, and faith in the process.

But if you make it through, I promise a meaningful dialogue. — Daria

In 1949, the Nobel Prize for Medicine was bestowed to Egas Moniz for introducing the lobotomy, a procedure intended to treat mental illness by — trigger warning — severing connections in the frontal lobes with an ice pick through the eye sockets. Moniz was inspired by research on chimpanzees who became “more cooperative”, and swiftly declared his method “always safe”.

Facing an overflow of psychiatric patients after the World Wars, lobotomies gained popularity due to their speed and low cost. The use of lobotomy on 50,000 patients in the U.S. was wielded as an economic solution to reduce overcrowding, and was often done without informed patient consent yet left them with lifelong consequences.

Contemporary

wrote of the time:By the time the Nobel was awarded, the downsides of lobotomy were well-known. That there was no evidence of long-term benefits in the majority of patients was a quibble in comparison to the most obvious problem: the lobotomised were often changed entirely.

Despite calls to rescind this Prize, the Nobel Foundation is a private institution and does not revoke awards. And so Moniz remains in the pantheon of Nobel Laureates.

In 1960, China was in the midst of profound transformation.

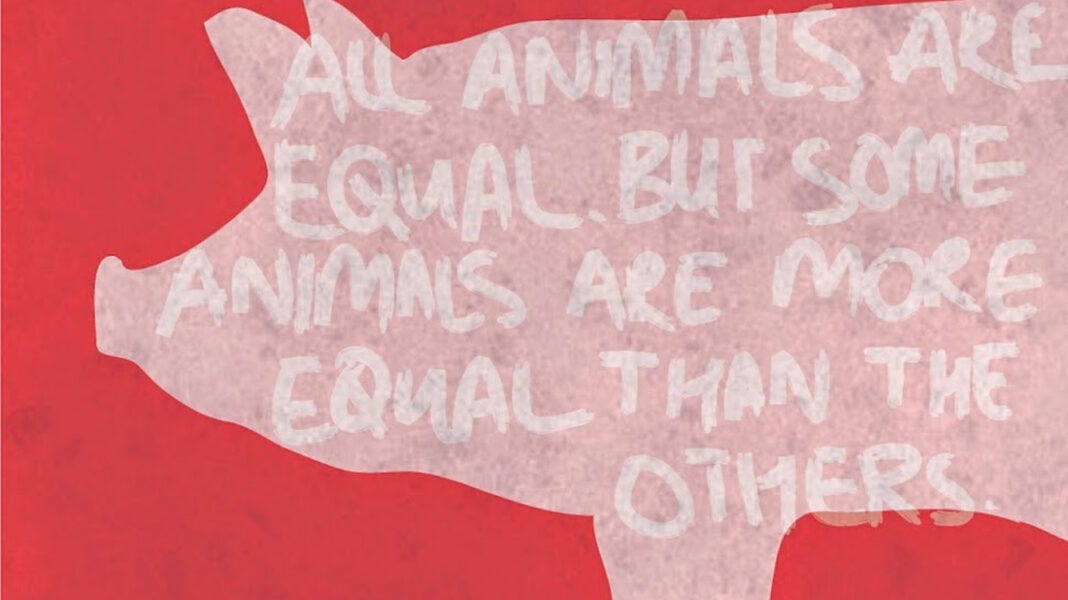

A “century of humiliation” had left its peasantry trapped between foreign imperialists who carved up coastal cities and landed gentry who controlled agricultural estates. Into this crucible stepped Mao, whose message of Chinese sovereignty wove together strands of nationalism, agrarian populism, and class struggle. His vision, known as the land reform movement (“土改”) quickly found fertile ground.

The vision of a strong, independent nation—where peasants owned the land they tilled and workers shared in industrial wealth—catalyzed such fervent hope that when he later called for rapid industrialization through the Great Leap Forward, millions embraced what they saw as their chance to transform China from a humbled nation into a modern power. Landowners and "bourgeois" citizens were named enemies of the working class; intellectuals and scientists became the foremost targets of reform.

Grain requisitioning and land collectivization disrupted farming. Local leaders, eager to please superiors, inflated crop yields, exacerbating food shortages and hastening what is now remembered as the "Three Years of Natural Disasters" (1959-1961).

What began as the socialist pursuit of an ideal society highlights the complex interplay of ideology, governance, and human toll. The impact of these policies have been documented across medicine, economics, and literature.

In 1989, a wave of liberal democracy swept through the Soviet Bloc.

Disillusioned by decades of communist rule, a desire for greater autonomy, prosperity, and liberty simmered just beneath the surface. That year saw the dismantling of Hungary’s “iron curtain” with Austria, semi-free elections in Poland, the fall of the Berlin Wall, leadership changes in Bulgaria, a peaceful transition of power in the former Czechoslovakia, and reached its crescendo in Romania.

On the morning of December 21, Nicolae Ceaușescu was determined to demonstrate his control with a mass rally in Bucharest. Ceaușescu's speech began as usual, until a shout from the crowd emboldened others. One shout turned into many. Then the shouts turned to chants. Ceaușescu thought the 10,000 people below his balcony were gathered outside to support him, before realizing he misjudged their loyalties.

The people had enough.

The antibodies were kicking in.

The dictator and his wife were tried and executed on Christmas Day, 1989.

After 42 years, communist rule had ended in Romania. Ceaușescu’s regime was an infection, a pathogen that suppressed the lifeblood of a nation: its people.

In medicine, immunity refers to the body's ability to recognize and defend against harmful substances: bacteria, viruses, toxins, foreign tissue, etc.

Innate immunity is the body’s biological line of defense: physical barriers like skin and mucous membranes, chemical barriers like enzymes and stomach acid, and inflammatory or cellular responses like white blood cells.

Adaptive immunity is an acquired skill: more specific, learned defenses that produce antibodies for specific pathogens, create memory cells to fight these threats, and get stronger with exposure.

Effective immunity relies on recognition of threats, mobilization of defenses, memory of past encounters, coordination across systems, ongoing vigilance, and the ability to discern what is “self” vs. what is “foreign”.

Why did immune responses succeed in Eastern Europe but fail in China? Reporting from summer 1989 reveals Gorbachev’s refusal to use force in contrast to Deng’s hardline approach. The former introduced policies of glasnost and perestroika to foster political pluralism and openness to reform; the latter crushed dissent at all levels, from top party officials to unarmed students.

How did the pathogen take over the host and suppress its antibodies? In Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China, Jung Chang wrote: “He understood ugly human instincts such as envy and resentment, and knew how to mobilize them for his ends. He ruled by getting people to hate each other. [He turned] the people into the ultimate weapon of dictatorship.”

The tides of history are constantly turning.

Democracy exists because we safeguard it; it is fragile as crystal and demanding as a flame. Citizenship is not a passive status; it is an active call for civic engagement. Our democracy rests not on the steps of Capitol Hill, but in the critical thinking of every American who believes in the promise of self-governance.